A debate between the current and the former mayor of Skopje, Petre Silegov and Koce Trajanovski, exposed how deep the ideological divide between the left and the right in Macedonia really is, and how it is often filled with ignorance and double standards.

Instead of discussing infrastructure, air pollution or other local problems, the discussion inevitably turned to how the development of the Macedonian nation is presented in the capital.

Silegov won the 2017 elections on the promise to implement the requests of the leftist Colored Revolution and remove monuments to historic figures placed across Skopje which the left objects to. Under Trajanovski and Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski, the reinvention of the city center included removing Communist era brutalist or modernist facades and replacing them with the neo-classical style or the pre-war style that was popular after the overthrow of the Ottoman Empire, when the Balkans was emulating Western architecture. The monuments and the changes to the city street names also reflected a much broader sweep of history, after decades of focusing on the heroes of the Communist party and those of the other parts of then Yugoslavia. This greatly angered the left which protested against the monuments to ancient era heroes and those on the right side of the ideological divide during the Macedonian national struggle.

Just give me administrative authority over the monuments and you will see how quickly I remove them, Silegov, in the third year of his term, fumed at Trajanovski.

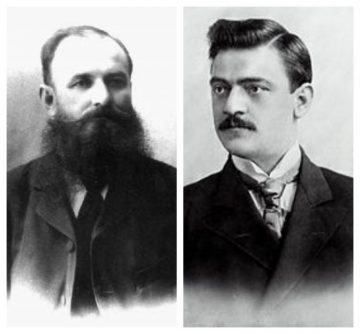

Much of his anger was fuelled by ignorance. He blamed one historic VMRO figure, Boris Sarafov, who was honored as part of Skopje 2014 after being ignored during the socialist Yugoslav era, as being the killer of another VMRO hero – Gjorce Petrov. One problem with this theory though – Sarafov was himself killed in 1907, while Petrov was killed 14 years later, in 1921.

The one monument that Silegov did remove is the one of Andon Lazov Janev – Koseto, who Silegov called a “murderer”. Trajanovski replied that, while Koseto’s role in the organization was clear, he was a companion of VMRO leader Goce Delcev and worked under his auspices, as well as those of Dame Gruev and Hristo Tatarcev, risking his own life many times to remove the enemies of Macedonian nationhood. Many of his victims were Macedonians, often those working for the interests of neighboring countries. So did many other VMRO heroes such as Jane Sandanski, Pitu Guli and Nikola Karev. Koseto was portrayed without any attempts to embellish his historical role – he was shown as slouching, grim an holding a dagger in his hand, as an accurate depiction of one frequently repeating portion of Macedonian history, but his monument replaced with a ginkgo tree by Silegov.

No similar scruples were shown by Silegov when discussing the retribution and murders perpetrated by the left, after their take-over in 1944, when the Communist party ordered the murder or arrests of innumerable national leaders and distinguished persons from the right. Monuments honored by the left, such as the monument to the liberators of Skopje placed next to the Government building, are never targets of criticism from the right, which has shown a far greater ability to move past the feuds of the past and accept the people who fought for Macedonia, warts and all.

Another issue that arose in the debate was related to the very Government building, which was redone from its rectangular Communist era style into a neo-classical building not unlike those across Western Europe. And yet Silegov mocked this replacement of facades calling them baroque – a term adopted by the left to ridicule the changing of the face of brutalist Skopje. “Turkey has no baroque”, Silegov quipped. But then, in fact, much of the architectural style of Turkey, which ruled Macedonia for centuries and whose cultural influence defined the region, has emulated the Western architecture.

Many former Communist capitals like Budapest, Warsaw, or the cities across former Eastern Germany, tried to restore their past glory after and do away with the grey facades of the past. Skopje’s attempt, under Trajanovski and Gruevski, to do the same, led to a huge increase in tourism and made the city resemble a European capital, but Silegov revealed that it continues to annoy the left to no end.

Comments are closed for this post.