Greek historian Spyridon Sfetas, who is part of the Greek team in the joint committee formed to alter Macedonian history book, detailed all the wins Greece scored in the arguments with Macedonian historians.

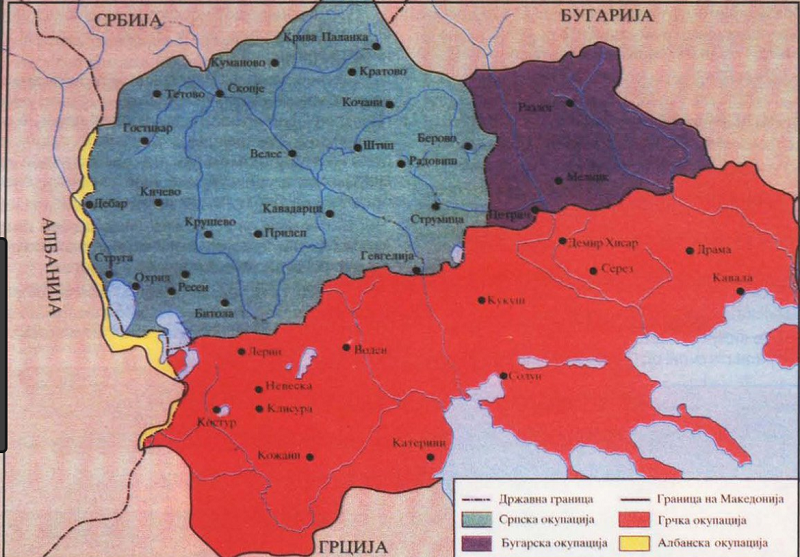

Sfetas told the Ethnos newspaper that the Macedonian side accepted to stop using the term Aegean Macedonia for the southern half of the region of Macedonia which Greece captured in the Balkan wars in 1912 and 1913. Macedonians call this region, around Solun-Thessaloniki, which includes cities such as Lerin, Voden and Kukus, Aegean Macedonia or “Belomorska Makedonija” – Macedonia by the White Sea. The region had a Macedonian majority population, but decades of assimilation, expulsions and especially population transfers with Turkey, Macedonia and Bulgaria made it majority Greek now, and it is actually seen as the hotbed of Greek nationalism and provided the winning margins for the conservative New Democracy party.

Sfetas adds that the Macedonian historians accepted that the Slavs had no connection with the ancient Macedonians – a position which Greek nationalists use to emphasize that they are the original settlers of the Balkans, while the Slavic speaking contemporary Macedonians are more recent settlers. Macedonian historians, Sfetas added, agreed that the ancient Macedonian culture was part of the Greek civilization, which in turn, has had a major influence of global civilization.

On the other hand, we don’t see a proposal from the other side that contemporary North Macedonia is the heir to the historic Macedonia from antiquity, Sfetas said.

Greek historians also insisted, and their Macedonian colleagues agreed under pressure, to accept that the Slavic peoples took the name Macedonia from the name of the Roman and Byzantian province, and not as result of their ties to the ancient Macedonian people. Some elements of the culture of the Slavic peoples, Greek historians insisted, have to be declared as Greek in origin.

Comments are closed for this post.